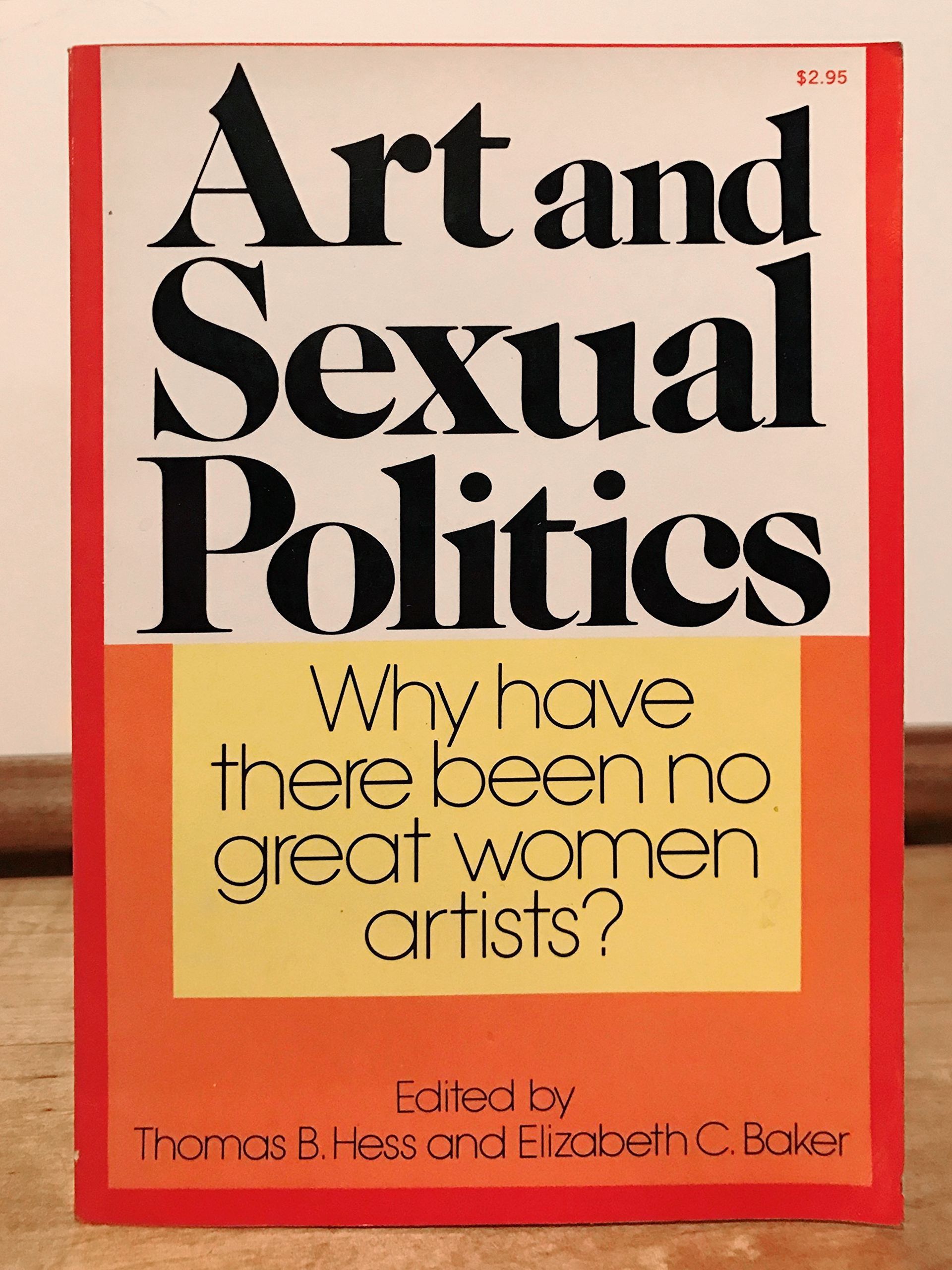

Which is ironic, given the scope of this topic. I wanted to focus on this because Nochlin’s essay is a major piece of writing and most major pieces of writing get lots of traction and subsequently end up being lauded as great works. It’s taken me far too long to finish writing this piece because apparently dipping into a 20-page essay in between two part-time jobs isn’t a wise idea. In the 2020s, at a time when ‘certain patriarchal values are making a comeback’, Nochlin’s message could not be more urgent: as she herself put it in 2015, ‘there is still a long way to go’.Today’s tirade (sort of) is brought to you courtesy of the famous and apparently feminist essay by Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? In a way it’s about her essay, but mostly it’s about the aura surrounding it, the reception given to it by a 21st century militantly feminist audience, and ultimately will devolve into a brief and mild discussion of sexism in the art world. ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ has become a slogan and rallying cry that resonates across culture and society Dior even adopted it in their 2018 collections. With reference to Joan Mitchell, Louise Bourgeois, Cindy Sherman and many more, Nochlin diagnoses the state of women and art with unmatched precision and verve. Written in an era of thriving feminist theory, as well as queer theory, race and postcolonial studies, ‘Thirty Years After’ is a striking reflection on the emergence of a whole new canon.

In this stand-alone anniversary edition, Nochlin’s essay is published alongside its reappraisal, ‘Thirty Years After’. Freedom, as she sees it, requires women to risk entirely demolishing the art world’s institutions, and rebuilding them anew – in other words, to leap into the unknown. With unparalleled insight and startling wit, Nochlin laid bare the acceptance of a white male viewpoint in art historical thought as not merely a moral failure, but an intellectual one. Instead, she dismantled the very concept of ‘greatness’, unravelling the basic assumptions that had centred a male-coded ‘genius’ in the study of art.

Nochlin refused to handle the question of why there had been no ‘great women artists’ on its own, corrupted, terms.

Linda Nochlin’s seminal essay on women artists is widely acknowledged as the first real attempt at a feminist history of art.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)